| Visit the Arthur Miller Writing Studio website: www.arthurmillerstudio.org. |

| The Arthur Miller Writing Studio organization in Roxbury, Connecticut sustains Arthur Miller’s legacy as a writer and an activist and helps to establish collaborative educational opportunities around the world. |

A Note on Arthur’s studio

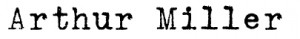

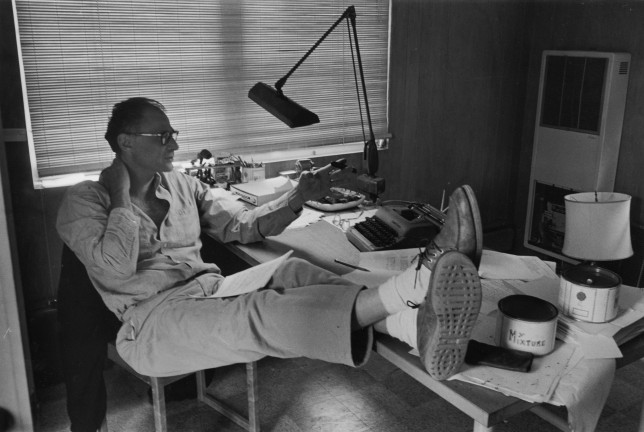

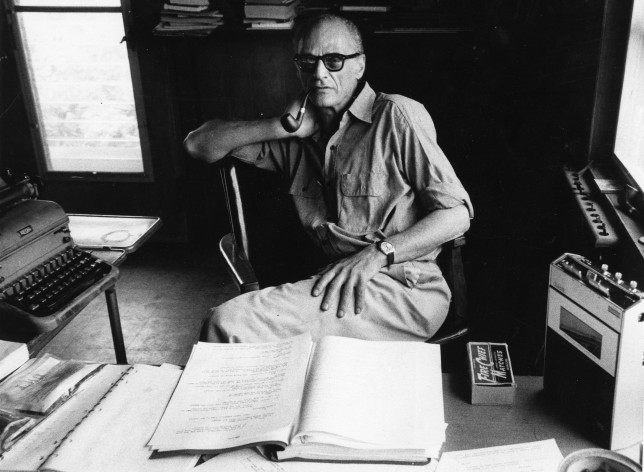

Arthur’s writing studio was a place of solitude and true quiet. He would walk up the grassy slope from the house after breakfast and work all morning. Later in the afternoon, he might garden with Inge or work in the yard or woods, pruning back or cutting trees. He might return to his studio, write in his journal, type a letter, or take a short nap on the daybed.

In the 1950s and 60s, he often wrote by hand in his notebooks and journals here. He also used a Royal typewriter for writing play drafts and scripts, later an electric typewriter, followed by an early personal computer and then a laptop. At some point a telephone was installed in the studio, as well as an intercom (which also connected from the house to the barn, where Arthur had his wood shop and Inge her studio spaces and darkroom).

Arthur made his first desk from a wooden door. He added a large desk with drawers after he expanded the studio structure. He made the third desk from heavy plywood to hold his early computer equipment and printer; he added a typewriter stand too. The desk chairs reflect different eras as well – from a faded pink 1950s molded fiberglass chair to a fabric-covered swivel office chair added in the late 1990s.

For almost fifty years Arthur kept everything in the studio filing cabinets that he was still working on or that he might return to. And he kept all his journals, his earliest letters and some of his earliest unpublished play scripts here too: the studio files housed the core of his unpublished archive. Black and white speckled school notebooks from the 1940s, spiral bound notebooks from the 1950s and 60s, overflowing loose-leaf binders of typed sheets from the 1970s and 80s, and 1990s binders of printed word processing files. From the first letter he wrote from college in 1934, saved by his mother, to the laser-printed journal pages of the early 2000’s – Arthur saved his most essential materials in this one place.

On the shelves he kept reference books for specific plays and project, volumes from the house library, and books he had carried with him from earlier places. Whatever he was reading at the moment might also land on those shelves. In later years he began keeping printed records of his (now) digital journals, bound in black binders, on those same shelves.

Arthur saw his journal writing as the one thing to which he devoted more of his writing life than any other single work. It was the one place everything fit. The studio itself stands as an outward manifestation of Arthur’s private writing life – the one place everything fit – where he could explore anything, aloud or in silence, with the narrow brook running below and the trees growing round.

(Julia Bolus, 2018)